‘The torture’s real. The time I did was real’: the Belfast man waterboarded by the British army

Liam Holden went to prison for 17 years on the basis of a confession he made after being tortured by British soldiers in 1972. Now the government is making it harder for people like him to get justice

Shortly after 2pm on 17 September 1972, a bright Sunday afternoon, six soldiers from the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute regiment were patrolling near the Ballymurphy estate in west Belfast. If you were a British soldier stationed in Northern Ireland at that time, the area around Ballymurphy was not a place to stand still for too long. Even when pausing briefly in a doorway, the young soldiers would sway from side to side, performing a life-or-death street ballet.

There were three soldiers on either side of the road. The last man on the left-hand side was an 18-year-old private, Frank Bell. When the patrol reached an exposed and potentially dangerous spot by a side street, the section commander, a corporal, quickly crossed before pausing to watch his men follow one at a time. As private Bell crossed the road, the soldiers heard the crack and fizz of an incoming high-velocity round.

Bell was flung backwards. Three of the soldiers leapt for cover. The corporal ran to Bell to drag him out of the open road. In a subsequent statement to the Royal Military Police, he said: “I loosened Pte Bell’s clothing and noticed he had a hole in the left side of his head which was bleeding quite badly.”

A local woman ran from her house with cotton wool, which the corporal used to try to stem the bleeding. The woman went back to her home and returned with a blanket. Despite local hostility to the paras, a number of other people emerged from their homes, and one of the soldiers later said in a statement that “some were sympathetic and trying to aid us as much as possible”.

An armoured ambulance arrived and Bell was taken to the Royal Victoria hospital. The other five soldiers continued with their patrol. At the hospital, after a blood transfusion, Bell was transferred to the intensive care unit, where, three days later, he died.

The year of Bell’s murder was the bloodiest of the Troubles. On 30 January, the day that became known as Bloody Sunday, 14 civil rights demonstrators had been fatally shot in Derry by soldiers of the parachute regiment. Six months later, nine people were killed in Belfast city centre and 130 injured when the IRA detonated 19 bombs in little more than an hour. There was a further surge in violence when the British army demolished makeshift barriers so that soldiers could patrol neighbourhoods that local nationalists had declared to be “no-go areas” for the security forces. The parachute regiment was sent into Ballymurphy.

Within the British army, the paras were, and are, a highly respected fighting unit in war, but they had a reputation for brutality that made them unpopular even with other army units serving in Northern Ireland. “Fantastic if you needed them to take hill-number-whatever from the enemy,” one Belfast policeman of the time told me. “Dangerous and disastrous if you were asking them to do what was essentially a policing operation in a complex and violently divided city.”

People in Ballymurphy say they had good reason to loathe the regiment long before Bloody Sunday. In August the previous year, 10 people had been shot dead in the neighbourhood over 36 hours; paras had killed at least eight of them. Almost 50 years later, a “legacy” inquest concluded that all 10 had been unarmed, innocent civilians who posed no threat to soldiers.

At their home in the Wirral, members of Frank Bell’s family told a reporter from the Liverpool Echo that he had been engaged to marry his childhood sweetheart, Christine, and that he had joined the army because he needed a job. He was the 599th person to be killed in Northern Ireland’s 30-year conflict, known as the Troubles, and the 108th soldier to die that year.

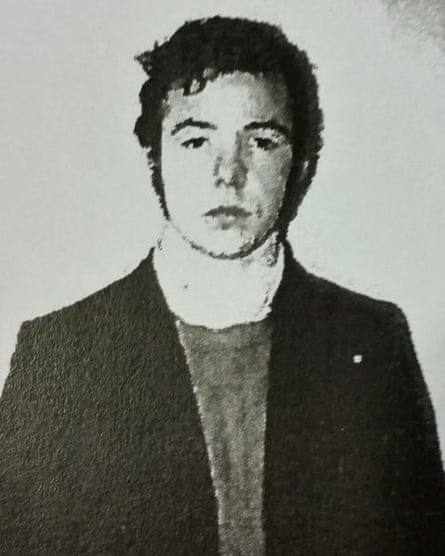

A few hundred yards south of the junction where Bell was shot, another 18-year-old lived with his family. Liam Holden, one of 13 children, had left school with no qualifications and was working as a junior chef at a hotel north of Belfast where his father had a job as a security guard. Like many people in Ballymurphy, he had some sympathies with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and had attended one meeting of the group’s youth wing, the Fianna, but did not take an oath of allegiance and never went back.

In the early hours of 16 October, a month after Frank Bell was shot, soldiers from the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment raided the family home and told Liam Holden’s parents that he and his older brother Patrick were wanted for questioning. The brothers were driven to a primary school in a nearby unionist neighbourhood that the army had partly requisitioned as a base. The brothers were led into a portable building and each placed in a small cubicle. After a while Patrick was released, but Liam was told that an informer had named him as the sniper who had shot Bell.

Holden was held and questioned throughout the night by soldiers from the parachute regiment. By the morning, he had made a confession. He was transferred to Castlereagh police station in the east of the city. There he was questioned by officers of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) for just 25 minutes. That evening, on the eve of his 19th birthday, he was charged with Frank Bell’s murder.

Today in Northern Ireland people live daily with the truth of William Faulkner’s famous line: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” When the Good Friday Agreement brought decades of violence largely to an end in 1998, the architects of that delicate deal knew that had they attempted to address the question of who was responsible for the many years of carnage, their treaty would never have been signed.

As a consequence, many people in the north of Ireland say today that the Troubles have not so much been resolved, as frozen. Even the most fundamental questions remain unsettled. Was it a war, or a series of crimes? Was the conflict essentially sectarian – Catholic v Protestant, nationalist against unionist – or was it a struggle between Irish republicans and the British state? There is little consensus over the legitimacy of political violence, the responsibility for that violence, or the motives of those involved. People cannot find a shared narrative to recall the past. Nor, at times, can they agree on a handful of words that might properly be used to describe it.

In the absence of a politically managed process to contend with the legacy of the Troubles, in the 25 years since the peace accord was signed, many victims of the conflict have begun pursuing justice through the courts. They have asked for new inquiries by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, pressed for inquests to be reopened, and brought lawsuits against the police or the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). By one recent count, there are about 450 outstanding complaints to the Ombudsman, 22 inquests before the courts, concerning 34 deaths, and about 575 current claims against the military alone.

Although the security forces were responsible for only around 10% of the 3,700 or so deaths between the late 1960s and 1998, the bulk of the complaints centre on the British army and the police. They concern allegations of unlawful killings, state collusion with terrorists and the use of torture.

In 2021, the British government responded to the growing number of lawsuits by drawing up controversial plans for a new Legacy Bill that will block compensation claims, stall new inquests into deaths during the Troubles, and prevent further investigations into police and army conduct. This legislation aims to draw a line under Northern Ireland’s troubled past, protecting former members of the armed services and preventing people like Liam Holden from having their day in court.

Holden always maintained he was innocent of killing Frank Bell, claiming that his confession was concocted by his interrogators and signed under duress. The MoD’s reluctance to produce evidence for its version of events, or to accept submissions to the contrary, have seemed at times to be part of a sustained effort to bury the past. It was not until last month, more than 50 years after Liam Holden was first arrested, that a judge finally delivered his verdict.

Holden’s criminal trial had opened in April 1973, seven months after Bell’s death. It was held in the grand Neoclassical courthouse known as Belfast City Commission, before the lord chief justice of Northern Ireland, Sir Robert Lowry. Because Holden was alleged to have murdered, as the indictment put it, “a soldier in the service of the Crown”, he had been charged with capital murder, meaning it was a death penalty case. In England, Scotland and Wales, hanging had not been used as a punishment since 1964, and had been officially abolished in 1969, but in Northern Ireland it remained on the statute books.

The evidence against Holden was entirely based on the confession made on the night of his arrest, first to the army, and then repeated when he was in RUC custody. There was no forensic evidence against him, and no more was heard of the anonymous “informant” who had identified him as the shooter. Before the case got under way, there was a form of trial-within-a-trial, in the absence of the jury, after Holden’s lawyers argued that his confessions should be ruled inadmissible. Two soldiers – a captain and a sergeant from the parachute regiment who had questioned Holden on the night of his arrest – gave evidence and were then cross-examined by Holden’s lawyers about the training they had received in interrogation techniques, and the way in which they had treated the teenager. They denied any wrongdoing, and the judge ruled that the confessions could be put before the jury.

Holden then gave the court his account of what happened in army custody. After being forced against the wall in a stress position, he said, he was punched in the stomach and burned with a lighter. When questioned about the shooting, he denied any involvement. At this point, he said, the sergeant called for a bucket and towel. Several soldiers held him down on the floor, a towel was placed over his face, and water was poured on to it. “It nearly put me unconscious,” Holden told the jury. “It nearly drowned me and stopped me from breathing. This went on for a minute.” This tactic, later known as waterboarding, was repeated three or four times.

Holden said he was then hooded, beaten, placed in a vehicle, and told he was being taken to an area on the outskirts of Belfast where the bodies of a number of murdered Catholic men had been discovered. He said he was told he was going to be shot. At this point, Holden said, he agreed to confess to shooting Bell.

Holden also told the court that before being handed over to the RUC, the soldiers had instructed him to repeat his admission to the police, threatening that they would bring him back to their base if he failed to do so. When he told the police what had happened to him, he said, they threatened to hand him back to the army if he did not sign a confession. The court heard that he had signed a statement confessing that he had fired the fatal shot using a .303 rifle with eight bullets in its magazine, which had been conveyed to him by a young girl. The sergeant said Holden had confessed because “he said he wanted to get it off his chest”.

At the time of Holden’s trial, in 1973, it was widely known that the British army abused its prisoners in Northern Ireland. The abuses were even officially acknowledged, although government ministers insisted that they fell short of torture. In March the previous year, the British prime minister Ted Heath had told parliament that there would be no further use of an interrogation method known as the “five techniques”: hooding, starvation, sleep deprivation, enforced stress positions and the use of loud noise. In combination and over a few days, they caused not only pain, exhaustion and distress, but the danger of severe psychological disintegration.

But the five techniques appear not to have been the only “aids to interrogation” being used in Northern Ireland. Following Heath’s announcement, Catholic priests began to gather statements from detainees who alleged that they had been abused in other ways while in military custody. People said they had been subject to electric shocks, or given drugs to keep them awake. There were also a small number of allegations of waterboarding. During a meeting at Downing Street in November 1972, while Holden was awaiting trial, the Irish taoiseach Jack Lynch raised the case of an epileptic man who was alleged to have been held down while in army custody, a towel placed over his head, “and water poured over it to give him the impression he would suffocate”. The record of the meeting shows that Heath replied that he “would not claim that all soldiers were perfect”, and that if complaints against them were found to be proved, “appropriate action was taken”.

There is no evidence that British soldiers were trained to use waterboarding when interrogating prisoners. But there is evidence that a number were exposed to the technique to help them resist torture if they fell into the hands of an unscrupulous enemy. In 1959, the army had made a 64-minute feature film, entitled Captured, which depicted British prisoners of war being waterboarded by their Chinese captors during the Korean war. The intention was to show the film to British military personnel. The filming was supervised by an officer who had himself suffered this torture. It remained classified until 2013, when it was made available to the British Film Institute.

Throughout Holden’s trial, soldiers from the parachute regiment denied waterboarding prisoners. And the jury at Belfast City Commission appears to have remained unconvinced by a defendant who said he confessed to murder because he had had some water splashed over his face.

After deliberating for just 90 minutes, the jury found Holden guilty. Lord Justice Lowry told him there was only one sentence he could pass: “The sentence of the court is that you will suffer death in the manner authorised by law.”

Holden was taken from the court to an underground tunnel that led to the city’s Crumlin Road jail, a vast, chaotic and filthy place that had been built in the 1840s. There he was walked to the condemned man’s cell. As he entered, Holden could see a bed along the left-hand wall, and in front of him were two windows, with a wooden cross attached to the wall between. To his right was a desk, and beyond that was an empty wooden bookshelf. Two prison officers were posted inside the cell at all times, to ensure Holden did not try to take his own life.

As a man sentenced to die, Holden had two small privileges: a black-and-white television set and a bottle of stout each day. He asked the prison officers if he could save up the stout and drink it all while watching the FA Cup Final: Leeds United, the favourites, were due to play in-form Sunderland. No, he was firmly told. You’ll drink them one bottle a day.

When I first spoke to Holden about the experience, in Belfast in 2011, he said he became numb and withdrawn following the sentence. He didn’t appeal, he told me, because he believed the justice system had been rigged against him. One of the prison officers, a fellow Catholic, would taunt him that it would not be long before they broke his neck, and would point to the patch of land inside the prison walls where the 17 men previously hanged at Crumlin Road lay buried. A white X painted on the wall marked where each man lay buried, but the graves remained unnamed.

Holden knew there was at least a chance his sentence would be commuted to life imprisonment: shortly before he went on trial, another man, a Loyalist named Albert Browne who had been convicted of murdering a police officer, had had his death sentence commuted.

A quiet, reserved man, Holden later recalled the dreadful uncertainty of those days. “Twenty-four hours a day of thinking, eating, sleeping, eating, sleeping, thinking. You’d think: ‘They’re not going to do it.’ And then, ‘Yes they are.’ Nor was Holden aware of what lay beyond the empty bookshelf: a spring mechanism ensured that it could be moved swiftly to one side, and beyond it was a concealed doorway that led to the gallows. The noose was a few paces from his bed.

After a month in the condemned man’s cell, Holden’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the man who had been appointed Northern Ireland secretary the previous year. In his memoirs, Willie Whitelaw wrote that he had once been “mildly in favour of capital punishment”, but had changed his mind over time. Hanging people in Northern Ireland at that time, in particular, “would only succeed in promoting the mayhem and killings which it was my purpose to stop”. After Holden’s sentence was commuted, capital punishment was abolished as a punishment for murder in Northern Ireland, bringing it into line with the rest of the UK. Holden had been the last person to be sentenced to death.

Holden was transferred to the recently built Maze Prison, 10 miles south-west of Belfast. His relationship with his girlfriend collapsed, and his mother, who had suffered a breakdown on the day he was sentenced, became very ill. He discouraged his family from visiting as he found their obvious distress deeply upsetting. He lost his religious belief. One of his brothers went to jail, convicted of a terrorism-related offence. Holden spent 17 years behind bars, before being released on licence in 1989.

When he emerged from prison, he found Belfast transformed. He was overwhelmed by the sight of new shopping centres, and the noise and colours in the city centre. He suffered nightmares and developed a fear of water. Not long after his release he was diagnosed as suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. Finding work was not easy for a lifer on licence. “Nobody would give me a job,” he said. “I was not allowed a job. Not allowed to do nothing.”

His new life was severely limited. He drove a taxi, but only for a short while. He needed to seek permission before changing address or leaving Northern Ireland to go on holiday. The police warned him on a number of occasions that he was facing threats from Loyalists. He said he was harassed by one particular police officer, who regularly stopped and searched him on the streets near his home, until he lodged a complaint.

There were moments of happiness too: Holden met a woman, Pauline. They married, and in 1993 a daughter, Bronagh, was born. But Pauline died in December 2000, and Holden was left to raise Bronagh and his stepson Samuel alone.

Bronagh told me that her father’s experiences left him remote and unable to express emotion. “He just wasn’t a very affectionate man,” she said. “He would talk about some of the good times in prison – the people, the pranks, the camaraderie.” But he couldn’t talk about his time in army custody. If it cropped up in conversation, he would quickly change the subject. “He wouldn’t be right for a couple of days after. He would just be in his own head.” He also couldn’t stand going into water. Bronagh’s uncle Patrick had to teach her to swim.

By the mid-1990s, it became possible to believe that a political settlement might finally bring peace to Northern Ireland. Eventually, after difficult and complex talks – and more than 120 further deaths between 1994 and 1997 – the Good Friday Agreement was signed in April 1998, bringing much of the violence to an end. The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) had been set up the previous year to offer an appeal process of last resort for those who said they had been victims of a miscarriage of justice, and Holden decided to appeal against his conviction. After examining his case, the CCRC referred it back to the court of appeal in 2009.

It finally reached the court in June 2012. Having researched British interrogation techniques for a book, I was asked to assist as an expert witness, giving a statement that explained how some UK forces personnel had been informed about waterboarding as part of their resistance-to-interrogation training.

The court was told that the CCRC had made a number of discoveries while examining confidential MoD files relating to Holden’s case. The CCRC found that at the time of Holden’s arrest, soldiers were operating under orders that anyone they arrested must be handed over to the police as soon as possible. The orders had been issued precisely because of concerns that soldiers were mistreating their prisoners. Despite these orders, Holden had been held and questioned by the army all night. The CCRC also learned that a few weeks before Holden was detained, in summer 1972, government lawyers had warned that arrest and detention by the army in such circumstances would be unlawful.

None of this had been disclosed at the time of Holden’s original trial. The court of appeal concluded that had the trial judge, Sir Robert Lowry, been aware of the contents of the MoD files, he may well have doubted the credibility of the two soldiers who had given evidence, and refused to allow the prosecution to rely entirely on Holden’s supposed confession.

At the 2012 appeal hearing, the prosecution said it would not be opposing Holden’s appeal. The court of appeal’s judgment remained silent on the issue of waterboarding. Nevertheless, the 40-year-old conviction was quashed. Holden and his children were jubilant. His lawyer, Belfast solicitor Patricia Coyle, said the family were “grateful that they are dealing with a quashed conviction, and not a posthumous pardon” for a hanged man. Asked by reporters about the way he said he had been treated in army custody, Holden said he regarded the term “waterboarding” as a euphemism, and abhorrent. “It was torture.”

In 2014, Holden applied for compensation for his 17 years of wrongful imprisonment. The Northern Ireland Justice Department accepted that the warnings in 1972 from government lawyers had completely undermined the trial process, and demonstrated that he was innocent. A judge concluded that Holden deserved £1.2m; the law required that compensation be capped at £1m. He was told that any claim for additional damages for the way he had been treated before signing a confession would need to be considered by the civil courts, and so his lawyers lodged a second claim.

The MoD indicated to the court that it had two witnesses who would rebut Holden’s allegations of torture – a retired parachute regiment officer who had questioned him, and a former detective sergeant. When Holden’s case for damages came to court in May 2021, lawyers for the MoD and the police stalled, maintaining that they had not yet been able to trace their two witnesses. A judge dismissed this claim as “an absolute load of nonsense”, but until the witnesses were found, he said he had little choice but to adjourn the case.

When the compensation case returned to court in January 2022, Holden’s counsel, Brian Fee KC, described it as “an extraordinary case arising out of one of the most serious miscarriages of justice imaginable”. Holden, he said, had been convicted because of “the wrongful, deliberate and malicious misconduct of the defendants [the MoD and Northern Ireland police]”. The retired army officer and detective, who had finally been located, declined to give evidence, which Fee described as “telling, given the seriousness of the allegations made”. He added that the MoD and police had “failed to provide a single shred of evidence to contradict [Holden’s] assertions”.

Lawyers representing the MoD and the Police Service of Northern Ireland fell back on an unexpectedly aggressive line of argument. Their position was that Holden had fired the shot that killed Bell; that his allegations of waterboarding were fabricated; and that he had confessed because he felt guilty. It was a defence that ignored the court of appeal’s ruling that Holden’s conviction was unsafe, the Northern Ireland Justice Department’s conclusion that he was innocent, and the absence of any witnesses to rebut Holden’s assertions. While giving evidence, Holden became unwell. He had to leave the courtroom and collapsed with a major panic attack.

By the time Holden’s suit for damages against the MoD first came to court in 2021, it appears that the mounting number of “legacy cases” was causing significant unease at the Ministry. Most of these cases focus on the actions of the security forces, rather than those of the IRA or Loyalist paramilitaries, shadowy bodies that are not so easy to sue. Legacy complaints and litigation not only posed potential problems for a small number of ex-soldiers; they also served as a steady reminder that the British state was a protagonist in the decades of bloody conflict.

While legacy cases, such as the litigation brought by Holden, were being hailed by some as a quest for truth and justice, they were disparaged by others as an attempt to distract from the murder and mayhem caused by the IRA.

Across Whitehall there was growing concern that the battle for Northern Ireland was now being fought over whose version of events would survive.

Government officials briefed the press in November 2021 about plans for the publication of an official British history of the conflict. “Ministers plan official account of the Troubles amid fears IRA supporters are rewriting history,” reported the Daily Telegraph. The government went further, unveiling plans in May 2022 for a new Legacy Bill that would prevent cases like Holden’s claim for compensation from reaching the courts, would stop fresh inquests into deaths during the Troubles, and would bar further police ombudsman investigations.

In May last year, four months after Holden gave evidence, the then Northern Ireland secretary Brandon Lewis told parliament: “The current system is broken. It is delivering neither justice nor information to the vast majority of families. The lengthy, adversarial and complex legal processes do not offer the most effective route to information recovery, nor do they foster understanding, acknowledgment or reconciliation.” Under his proposed new law, a “truth recovery” body would be established with the stated aim of “recording and preserving” experiences of the Troubles, for future study. Anyone co-operating truthfully with it could expect immunity from prosecution. Subsequently, Lewis wrote that he hoped his Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill would shield former soldiers and police officers from being “hounded”.

While groups representing army veterans welcomed the move, the Bill succeeded in uniting political representatives of Northern Ireland’s two communities against it – a rare achievement. They protested that the measure will deny justice to the hundreds of victims of the conflict still fighting for a settlement. There are concerns that the Bill will not only bring current criminal prosecutions to a halt, block inquests and end litigation, but even undermine the Good Friday Agreement. In October 2022, parliament’s joint committee on human rights urged the government to “reconsider its approach”. The Council of Europe has also expressed concerns about the Bill.

At the time of writing, the Legacy Bill has sailed through the Commons, and is being considered by the House of Lords. Peers are deliberating on a series of amendments before sending it back to the Commons.

In Liam Holden’s case, at least, the outcome of the Legacy Bill won’t matter. On 24 March 2023, a high court judge in Belfast, Mr Justice Rooney, delivered his 61-page judgment. “I am persuaded, on the balance of probabilities, that the plaintiff was subjected to the acts of impropriety as alleged against the defendants,” he said. “It is my decision that the plaintiff was subjected to waterboarding; he was hooded; he was driven in a car flanked by soldiers to a location where he thought he would be assassinated; a gun was put to his head, and he was threatened that he would be shot dead. It is the view of this court that the said ill-treatment caused the plaintiff to make admissions and a confession statement.”

Holden, the judge noted, had steadily maintained his account for almost half a century. “Despite the passage of time, in my judgment there has been a constant thread of consistency in the plaintiff’s evidence to this court when compared to his previous accounts of the events.”

It was the army, rather than the police, that faced the greater criticism in Rooney’s judgment: “I conclude that the plaintiff was exposed to humiliation and degradation and that the soldiers behaved in a high-handed, insulting, malicious and oppressive manner.” Holden’s estate was awarded a further £350,000 in damages.

During his long battle to clear his name and win compensation, Holden had spoken occasionally about his need to be heard, and to be believed. He wanted the courts to acknowledge what had happened to him. “The torture’s real, the sentence was real, the time I done was real,” he said in an interview, adding: “I’m real.” He thought often about the graves of the men hanged at Crumlin Road. “I could have been one of them, in an unmarked grave up against the wall. With a wee white cross to state that that is a person. A person – not Liam Holden – a person.” After giving evidence in January last year, he had thanked Rooney, simply for hearing his story.

But the judgment came too late for Holden. In poor physical health with lung problems, and with his PTSD symptoms growing steadily worse, he had been admitted to hospital last August after suffering weight loss. Shortly after he was admitted, he had a stroke. At 6am on the morning of Thursday 15 September, Holden died. He was 68.

This article was amended on 11 April 2023 to reinstate a reference to the Ballymurphy massacre of August 1971 that was cut during the editing process.