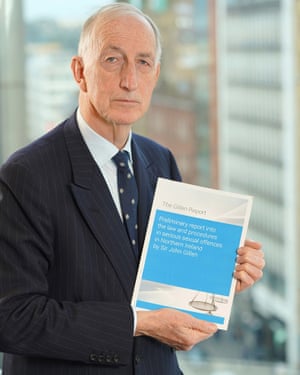

Northern Ireland rape case review calls for legal representation for complainants

Sir John Gillen’s interim report also recommends limiting public access to courtrooms

A retired senior judge has called for an overhaul of the way rape is dealt with by the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland, in a move that could have profound implications for the rest of the UK.

In an interim report, Sir John Gillen has called for a series of measures likely to be viewed as controversial by some, including limiting public access to court in rape trials and providing complainants with legal representation.

Gillen – who said he wanted to leave “no voice unheard” – is looking at how Northern Ireland deals with serious sexual offences as part of an independent review. There was an intense public debate and protests following the acquittal of two Ulster Rugby players, Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding, in March after a nine-week rape trial in Belfast.

The draft report highlights a series of failings: although 45% of defendants charged with rape were convicted of an offence, only 15% were convicted of rape. Northern Ireland’s conviction rate for non-sexual offences is 88.2%.

The review is ongoing, but Gillen has made a series of interim proposals, including that:

- Victims of serious sexual offences should be offered legal representation, in some cases.

- Juries should undergo training before the start of a trial to make sure they are aware of pervasive rape myths.

- There should be a shift towards an explicit expression of consent so that a lack of resistance was not understood to equal consent.

- Jurors who access social media about the trial should face harsher penalties.

The report also suggests banning the public from rape trials, limiting access only to the people directly involved and the press. Citing the Ulster rugby trial, Gillen said the public attention had been huge with the complainant forced to give the most intimate details in front of more than 100 people.

“Complainants hate it, they find it a real burden … and that contributes to people not coming forward,” he said.

The former judge said he was not persuaded that defendants should also retain anonymity in sexual offence trials – as they do in the Republic of Ireland – because it was likely to stop collaborate evidence emerging.

Speaking to the Guardian before the interim report’s publication, Gillen said that he had spoken to more than 200 organisations and individuals, including complainants, defendants, members of the judiciary, statutory and voluntary organisations and drawn from the methods used in 15 other countries. He said that meeting complainants and talking to them about their experiences was “one of the most harrowing experiences” of his life, and that it would drive him on to try and improve the situation.

Many of the report’s recommendations will be welcomed by campaigners, but Gillen dismissed the argument that his proposals could be seen as shifting the balance of power towards complainants in rape trials.

“We want to increase the ability to get a fair trial, and many of my suggestions would benefit the accused as well,” he said.

Survivors’ groups are likely to welcome Gillen’s proposal that complainants asked to hand over certain records, such as medical histories, should have legal representation.

“The right to have legal representation to oppose cross-examination on previous sexual history and to oppose disclosure of personal medical records seems eminently sensible,” the interim report says.

Gillen added: “Many complainants said to me ‘I didn’t realise I was on trial, and I didn’t realise I didn’t have any representation. Often [the lack of legal representation for complainants] comes as a bolt out of the blue and that has to change.”

Although Gillen said he was not convinced by arguments that juries on rape trials should be replaced with a judge, he was “open to dissuasion”.

“I still think the strength of the jury system can combat the problems we currently face,” he said. “But there is no doubt that there is a growing belief , particularly among young people, that a jury should be replaced by a judge or by a judge and two lay people such as we see in family courts and aspects of youth justice.”

Juries were influenced by rape myths pervasive in society, said Gillen, who suggested that a large-scale publicity campaign to educate the public was needed. “Jurors don’t land from the moon, they are people like you and me,” he said.

Gillen said that delays in cases getting to court were unacceptable. In Northern Ireland the average wait from report to trial was 943 days, compared to 558 days in England and Wales.

The report also calls for reforms to the process of disclosure – the obligation of prosecutors to pass on material that may undermine its case or support the defence – which caused delays that Gillen called a “blight” on the criminal justice system.

“The current system is being operated in a completely outmoded, inadequate and inefficient manner, bereft of modern technology and sufficiently skilled operators,” states the report. Disclosure was too often seen as an add-on at the end of investigations, it said, adding that there was a need for an injection of resources to train specialist police officers and that defence barristers had to be involved in the process from the beginning so the parameters of the extent of disclosure could be set early on.

Sarah Green, the co-director of the End Violence Against Women Coalition, called the report “bold”, and urged the government to take strong action.

“There is massive worry and anger about the state of justice for rape throughout the UK. We hope that the home and justice secretaries in London, all judges, police and prosecution leaders, support agencies and everyone with a connection will read and consider what is set out in this review,” she said. “We have to get to a different place on our entire response to rape because at present the crime is effectively decriminalised in some aspects.”

The Guardian

22.11.2018